Summer Reads

One thing I like about living with roommates is that we have a collective bookshelf. Our individual rooms aren’t that large, so to save space we started putting all of our books together. With the time that summer break frees up, I’ve managed to finish a couple, all of which are good leisure reads i.e. not overly long. Though the books and their characters wildly differ, there’s a loose thread stitching the works together: their lucidity. I always prefer concision in writing, partly because I’m a lazy reader, but mainly because most feelings can be sharpened down to a few hard-hitting words. Even though these novels are digestible enough to gulp down in a few free afternoons, they’re also rewarding enough to leave lasting impressions which reverberate beyond that, so they make great choices for summer reading.

.

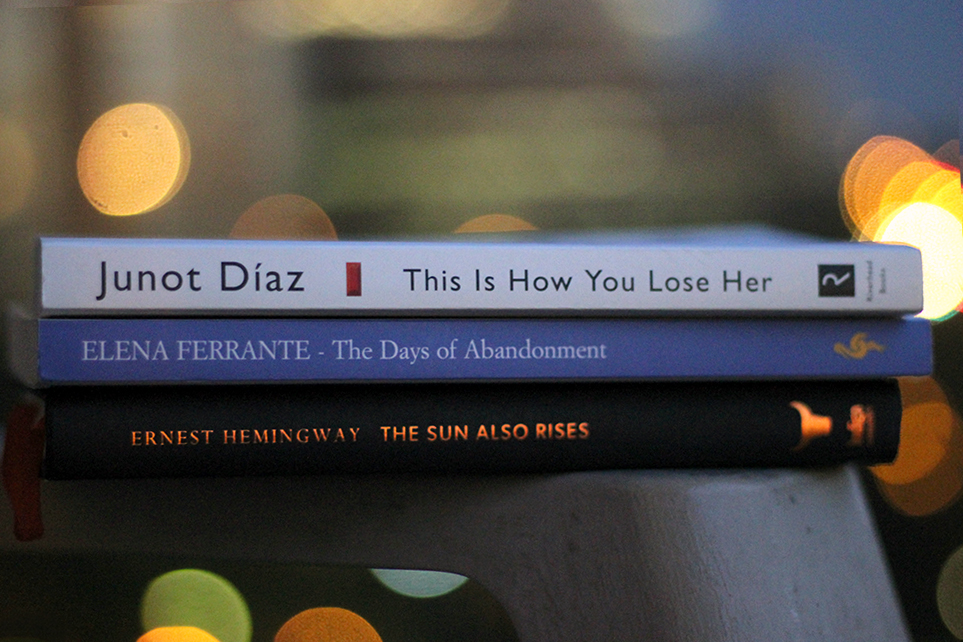

This Is How You Lose Her – Junot Díaz

This is a collection of nine short stories mostly featuring the hopeless romantic exploits of Yunior de Las Casas, a Dominican-American character who’s a semi-autobiographical figure of Díaz himself. The last short story, ‘The Cheater’s Guide to Love,’ begins like this:

“Your girl catches you cheating. (Well, actually she’s your fiancée, but hey, in a bit it so won’t matter.) She could have caught you with one sucia, she could have caught you with two, but as you’re a totally bat shit cuero who didn’t ever empty his e-mail trash can, she caught you with fifty! Sure, over a six-year period, but still. Fifty fucking girls? God-damn.”

What a catch! At this point we’re well aware that Yunior’s kind of a jerk – charming and sensitive and flawed, still one nonetheless. He’s a serial cheater whose heartfelt longing manages to endear women to him, despite how his understanding of women is, as Díaz describes, “pretty fucking limited.” Although he’s aware of his machismo, he does nothing about it, chalking up his flaws to some embedded genetic code: “You are your father’s son and your brother’s brother,” he shrugs.

Unable to negotiate the demands of a romantic relationship, Yunior repeatedly experiences losses of his own making. To him, patterns of behaviour are inherited and unchangeable, so naturally male infidelity is inevitable. Not that he’s callous – or at least, 100% so. More like 38%. He’s capable of great love and great regret; he’s incapable of doing anything about his “lying cheater’s heart.” Before finishing the book, the excuse would have made my eyes roll so far up my head that they’d permanently detach from the optic nerve. But things can change after just a few short stories, after which I found myself really adoring Yunior, to much internal groaning. A lot of the book’s humour is a result of Yunior’s character. He’s incredibly funny, not cause he’s some jokester, but because he’s so absurd. There are times when he’s so poignant, so moving, you wonder just how someone could have such profound observations. Then right after he’d say something like: “Miss Lora was too skinny. Had no hips whatsoever. No breasts, either, no ass, even her hair failed to make the grade.” Oh sweet Yunior. What to make of him?

The polarity and sheer ridiculousness of his voice drew me in right away, but it’s hard to swallow everything he says with an open smile and a thumbs up. He never attributes complex emotions to women; their inner lives don’t exist at all to him. While in a lot of cases this quality could be the mark of a virulent misogynist, in this book, it strikes me more as being about the stunted emotional growth of a little boy. Yunior’s trying his best to navigate his life but he hurts people along the way, like everyone else. But the reason I think his emotional growth is a bit stunted is that he never does anything to change, and so as a result, he continues to be the one who suffers the most from his actions. That’s why he’s equally despicable and lovable. For me at least, the tension of his character is why these stories can continually pull you in.

.

The Days of Abandonment

The Days of Abandonment – Elena Ferrante

I found this book frightening. There’s no demonic haunting, no grotesque murder, just a marriage and its dissolution. A woman spirals down into an “absence of sense” after her husband leaves her and their two young children for a 20-year old girl. Losing grip on reality, she traverses through the buried tunnels of her psyche to assail everything exalted about motherhood and marriage.

Originally written in Italian, the novel apparently caused a stir when it was first published in 2002. It’s ugly and honest, sparing no regard for social niceties that the main character Olga once observed. She made an effort to be cultivated but her husband abandoned her anyway. So she screams: “I don’t give a shit about prissiness. You wounded me, you are destroying me, and I’m supposed to speak like a good, well-brought-up wife? Fuck you!”

What I found frightening wasn’t the husband Mario’s fickleness or callous disregard or abrupt loss of love – it was his power to make Olga believe that she was utterly destroyed by his desertion. To Olga, Mario took everything. In marriage, she became a pillar of loyalty supporting his wishes, demands, and career, all at the expense of her own. Motherhood stripped her of sensuality. Her body became “almost absent flesh that tasted of milk, cookies, cereal,” no longer her own, instead subsisted on. For her sacrifices she expects a continuation of the normal order at the very least. When Mario desecrates domesticity, her rage commences.

Olga’s anger at Mario isn’t cold, calculated. It’s fresh grief. We follow her thought processes as her logic breaks down, as her identity crumbles into discrete parts. At its core, the book is about despair and where it takes her, but more importantly, how she emerges from it. The process is long-lasting and disorienting, but ultimately, Olga’s descent and subsequent lucidity shows that it’s essentially that: a process.

.

The Sun Also Rises – Ernest Hemingway

Sunset over North York

I’ve read this book before but on second reading, I was surprised at how much I missed the first time. The story is pretty simple. A group of American and British expats in Paris travel to Spain to watch the bullfights, but all the men want the same woman and she refuses to commit to any of them. Spicy. Naturally, tensions build up, explode, then fizzle, and there’s a lot to say about unfulfilled expectations and the fleetingness of feelings. But on top of it all, there’s something more chilling about the story and the way Hemingway writes it: everything about the characters’ lives is empty.

Published in 1926, the novel focuses on the ‘Lost Generation,’ i.e. those who came of age during World War I. For much of this generation, day-to-day life had lost its meaning after the war. In The Sun Also Rises, the characters aimlessly wander, hopping around from place to place in a glitzy version of grown-up musical chairs. They spend their days drinking, socializing, and traveling. It seems fun and stylish at first but it soon becomes a bit off-putting. All of it is for distraction and none of them are happy: “You can’t get away from yourself by moving from one place to another,” the narrator Jake says.

While the novel is emotionally charged, it’s easy to miss what’s going on in Hemingway’s writing because he describes so little. Most things are left unsaid, like who feels what toward whom, and why. Even though Brett, the sole woman, has a series of affairs that causes violent outbreaks of jealousy in the men who care about her, emotional states are rarely elaborated on. The writing avoids sentimentality, like it’s repelled by impassioned declarations of feeling. This style appeals to the harder side of me, but aside from personal preferences, the book’s verbal restraint makes for a generally more engaged reading experience. It’s up to the reader to detect the tension driving the dialogue, to figure out what the characters really think and feel.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post